The Story

It was Timothy Leary, the “Pied Piper of the Psychedelic Sixties” who, in reference to LSD (the common abbreviation for d-lysergic acid dyethyl amide, also shortened to simply “acid”) coined the phrase: “Tune in, turn on, and drop out.” As this new era of drugs, sex, and rock’n’roll unfolded, Leary became its chief spokesman and self-appointed publicist. It has often been joked that if you remember the Sixties, you weren’t there.

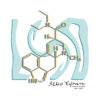

Yet it was the brilliant Swiss chemist, Albert Hofmann who discovered LSD decades earlier, and that’s where the story really begins. LSD was first synthesized by Hofmann in 1938 while working in the pharmaceutical department at Sandoz Laboratories in Basel, Switzerland. His interest was in the chemistry of plants and animals, and during a search for a circulatory stimulant in the fungus ergot, commonly found on rye bread, he investigated lysergic acid derivatives.

Hofmann discovered the psychedelic properties of LSD five years later by accidentally absorbing a small quantity from an earlier project he had set aside, with strangely fantastic results. He then decided to carry out an experiment on himself, deliberately ingesting .25mg of LSD. His subsequent hallucinogenic ride home on a bicycle April 19, 1943 is now a classic in psychedelic lore, called “Bicycle Day.” He reported his finding to his boss, Arthur Stoll, whose name is included on the patent. Follow-up testing by three lab assistants collaborated the “extremely impressive and fantastic experience.” Hofmann had discovered the extraordinary potency of LSD: the world would never quite be the same.

LSD, under the Sandoz trade name Delysid, was used as a therapeutic aid in psychiatry in early years; the patent specifically states that these “new amides are valuable therapeutical products.” Later, through the 50s and into the 60s, the U.S. government’s Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) ran a clandestine research program called MK-ULTRA, where doses of LSD were administered to people for mind control testing purposes—often without the recipients’ knowledge (and in violation of the Nuremberg Code that the U.S. agreed to follow after World War II). LSD was eventually dismissed by the CIA as being too unpredictable to be of use.

In 1963 after the Sandoz patent expired, LSD escaped from the lab and became the most widely-used psychedelic drug of choice. It appeared on the open market in many unique forms, from infused sugar cubes, to Orange Sunshine tablets, Microdots, Blotter, and Windowpane. Other names, like Owsley’s (the underground chemist known as Bear, who was also the “Wall of Sound” engineer for the Grateful Dead band) White Lightning, Monterey Purple, and Blue Cheer were colorful descriptions of the drug’s anticipated “clarifying” effects.

LSD’s psychological effects, known as “trips,” varied greatly from person to person, and even with the same person in different environments and times. For many, its distortion of reality was a fantastic hallucinogenic, transformative, and even spiritual experience; for others it was frightening or overwhelming, and for still other unfortunate souls, it was a nightmare in hell that left them with lifelong recurring psychosis. In October 1966, LSD was declared illegal in California.

It is impossible to know how deeply intertwined with the culture of the 60s LSD really was, but its mark on vocabulary, fashion, art and music during that era, to this day, connotes “Acid Trip.”

Hofmann called LSD “medicine for the soul” yet he felt it had been misused by the 60s counterculture, and thus was unfairly vilified by the establishment after more than 10 years of successful use in psychoanalysis. He did admit that if misused, LSD “could be dangerous.”

In 1980 Hofmann wrote an autobiographical account of his experience with LSD and called it “My Problem Child.” He died in 2008 of natural causes, having lived to be 102 years old.